A Storm of Dust (Ch25)

Theda gears up to go home and prepares to forget she ever came to Fort Riley, but even the best laid plans get derailed.

First Chapter | Previous Chapter | Chapters Summary

Why did my father burn those photographs?

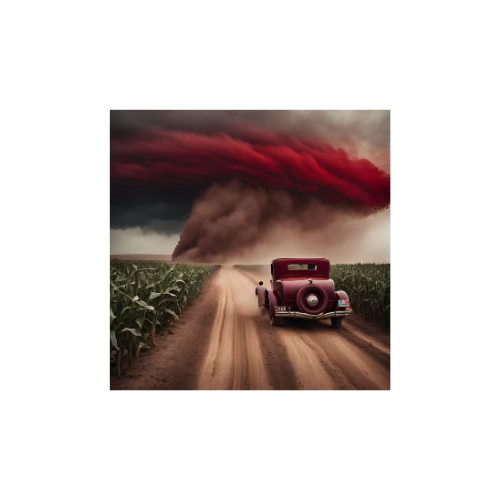

Theda Evora stood on the front porch as night returned in apocalyptic tones. The dust storm formed a roiling amber wave that cleaved the sky, sending flocks of field birds ahead as squawking doom messengers. The wind toted the rancid odor of yesterday’s burnings but suggesting that a new fire had been set in the fields and was now, if she had to make an educated guess, a poor addendum to this morning’s weather forecast. The dust devoured the cornfields and the sun eventually fell behind its equally fascinating and terrifying curtain. A red car emerged from the cloud and sped down the dirt road, stopping at the foot of the porch.

Behind her the front door slammed open and Margaret Evora passed Theda, limped down the steps, leaning on her walking stick more than she had in the past few weeks. “Hurry, Theodora! In the car!”

“Let me take that for you, ma’am,” the driver practically fell from the car and hurried to help her mother. Theda recognized the car. It was the cherry red Stanley Motorcar that collected them from the train on their first day in Fort Riley. Only this driver wasn’t the dashing Billy Rankin or the motorcycle riding Asa Jackson. That was only a few days ago, but it seemed like a relic from a long past, as if it sliced through time.

She laughed weakly. Slicing through time. Like one Mr. Conlin of the year 1946. And Private Jackson is dead.

“Nothing is humorous about this, I assure you.” Violet, in a foul mood from the moment she woke up over not being about to say farewell to Billy, pushed past her and threw an elbow into her side. “Trousers! Unbelievable. You cannot travel like this! What will people say?”

“They’ll say,” her sleepless eyes glancing sideways, “that this girl wearing the black trousers is the strangest creature they ever saw. And they’ll leave me alone.” The black trouser suit had been controversial when first purchased, but oh, how it now came in handy. The matching jacket fit perfectly over her white blouse, concealing the holstered pistol that poked her ribs.

The cloud expanded over the cornfields and Violet squeaked. “Let’s go, Theodora.” She squeezed her sister’s arm and descended.

Theda looked over her shoulder. The last thing she did in the house was to poke around in the fireplace ashes. Nothing legible remained, not even the hint of a letter or the corner white boarder of a picture. The missing Dr. Collins hadn’t hidden those photographs of dead soldiers deep in the closet for the fun of it. He thought he was coming back to that house. He never made it.

She sat down in the Stanley’s backseat and slammed the door shut, closing her eyes at the same time. No! Eventhinking about it felt like a betrayal of her father. She had promised a trouble-free return to Philadelphia, and deviating from that plan was out of the question. In her mind’s eye her father’s face, disappointed and angry, presented itself from where she was certain it would lurk forever, waiting to spring and reinvigorate her shame. She flushed hot in her cheeks and fainting felt like a real possibility. So was crawling under the seat to make herself as small as possible. You owe me, he had said, and she did. The problems of a missing doctor and his macabre post-mortem photographs were for someone else.

Phantom fingers of wispy dust circled the Stanley and soon the windshield displayed a murky world washed over with swirling brown particles.

“Theda, did you get dust in your eyes?” Margaret asked from the front passenger seat.

“No, I’m fine.”

“Good.” She turned to the driver. “What is this dust anyway? I’ve never seen anything like this. I’ve never smelled anything like this!”

“This is Kansas, ma’am. Dust storms kick up here every now and then. That terrible odor is the manure burning. They do that, and burn the dead animals, too.”

“Dead animals? Why?” Violet pulled her scarf tighter over her face, her amber eyes watering from the stench.

“Animals turn up sick. This morning they found some sick hogs and had to put them down. Heard about it when I was getting ready to leave to collect y’all. Sick pork ain’t good eatin’.”

Were those boys in the photographs gassed? Harold alluded that Collins had something to do with gas. But she didn’t know what a man looked like who had been gassed, and those marks around the faces of the men in the photograph weren’t anything she had seen before.

Stop! She raised her gloved hands to her face as if she could physically pull the thoughts away. She was tired. Too tired for a twenty-year old woman who had a bright future, a future she almost obliterated by following the wrong people.

The crowded train station stank of disappointment, and from the expressions on the faces of the waiting passengers, growing anger as well.

“As soon as I saw that dust cloud, I knew we’d never get out of here!” Violet tapped her gloved fingers on the long wooden bench in the Fort Riley train station.

“Hush, Violet. There’s nothing you can do about the weather. Better men have tried,” Mother replied wryly.

“We could stay another few days,” Violet suggested with a wide-eyed innocence that Theda almost laughed.

“Good effort, my dear. But your father was adamant that we go home, and go home we shall. I can’t say I’m sad over that decision, either,” Margaret tapped her walking stick on the raw wooden floor. She watched the ticket counter, where several men negotiated future tickets with exasperated travelers. Behind them a young man hunched over the wire, tapping with rhythmic urgency. He clicked away at the longs and shorts of his code. Theda didn’t know Morse, but it was not hard to imagine. Dust storm…how long…delay…delay…delay…

Violet asked their mother about when she would be able to visit Kansas again but Theda had had enough. If she heard one more sentence about the obnoxious Billy Rankin, she’d explode. “I’m going closer to the wireless operator. I’ll return when I get news of the train,” she slid from the bench and walked off.

She sauntered over to the counter but there was no news to overhear that she didn’t already know: that the train was at least two hours delayed due to the storm which had blanketed the area, making it difficult for the conductors to see. Not willing to go back to her seated area, she walked over to a large side window facing the tracks close to the back entrance. She spied an empty corner with the same type of wooden bench, although this one was much shorter and had only one man seated on it, huddled under his overcoat, his hat pulled low.

The window lost its function of portal to the outside world. The stinking dust flew past in dirty ribbons, hazing outside objects into fuzzy fragments. The road beyond the tracks was barely visible. Phantom autos drove at a snail’s pace, their size the only identifiers as either military truck or civilian car.

“In Kansas, dust storms are a common occurrence. When you live according to the earth’s cycles, you grow used to it by the time you’re old enough to peek over a windowsill. I can tell a city girl when I see one. No need to be afraid. All storms come to an end eventually.”

She had heard that German or Dutch accented voice yesterday on the other side of the door in the General Building. He was dressed entirely in black and his long white beard touched his chest. Mennonite. He’s Van Horn’s father. Not even twenty-four hours ago he was fighting for the right to collect his dead son’s body. His red rimmed ice blue eyes were large under the razor-sharp fringe of white hair poking out from his hat. His eyes settled briefly on her trousers, then he turned, expressionless, back to the swirling window.

“I wouldn’t be surprised if a plague of locusts follows,” she sat next to him and dug her nails into her upper thigh because her next words were mercury falling from her lips. “I heard you yesterday in the General Building. I was in a different room. My father is one of the doctors”

Van Horn’s head turned. “His name?”

“Dr. Harold Evora.”

“I don’t recall speaking with him. Only Dr. Harris. He treated my son. He informed me of his death.”

“Your son was Caleb Van Horn?”

He startled. “Yes. How would you know?”

“I was at the Infirmary when they brought him in.”

“Are you a nurse?”

“No, but I’ve studied under my father for some time.”

“And what was my son’s condition then? Do you know?”

“He was unconscious,” she started, and thought of the white feathers glued to his boots and the dried mud smeared across his face and into his hair. Tell him everything. I’m leaving. This man deserves the truth. “From what I understand, your son was a victim of vicious harassment. I believe it possible that he was left outside for most of the night.”

He nodded slowly. “That does not come as a shock. It is happening to all our enlisted sons. We live by the word of the Lord, and that does not mean half measures. When we’re asked to pick up arms against our fellow man, we refuse. When we’re forced to pick up arms against our fellow man, we continue to refuse. We suffer the consequences of those actions. I’m proud that my son fought them. To the end of his life.”

“I’m so sorry. These times are not kind to those who stand on the opposite side of the war.” She remembered the two faces of Maxim. The young that she had held between her palms, and the one in Conlin’s photograph, still young but already ancient.

“They buried him. I cannot take him home to his mother. A disease that spreads rapidly must be quelled instantly. I understand.” Hesitancy in his voice.

“What did he die of?”

“Dr. Harris said advanced consumption. Apparently, he had had it for some time.”

“Tuberculosis spreads rapidly…” she started, then stopped. When she saw Caleb Van Horn in the Infirmary and listened to his breathing, the signs of labored breath weren’t there.

And she knew what it sounded like. Seven years earlier, the Evora family toured Europe. One fine afternoon in Paris, Theda came upon a beggar sprawled in a doorway. Mademoiselle, s’il vous plait, l’argent? Then punctuated the sentence with a series of guttural coughs. Harold Evora pulled her away so fast her arm ached for hours. Keep away from him! Tuberculosis fills your lungs with fluid. Bloody coughing until the end, when you cough yourself into Elysium. If you catch it, you’ll die.

Caleb Van Horn’s lungs were clear. Consumption? It was impossible. Tuberculosis took months, sometimes years before the victim died. Anyone man who contracted it would not be allowed within a mile of an Army camp.

“The men here do not seem to have any concern for my son’s death,” the elder Van Horn went on. “But then why would they? They are sending their men to death. What does one life mean to them when they have thousands to sacrifice?” He stared at the dust again, water welling in his eyes but not falling. “When there is illness in our town, we quarantine. I’m sure the Infirmary must have been quarantined as well.”

“No, that building was not quarantined. Not to my knowledge.” His lungs were clear. And no body to bring home.

“Then one of a reasonable intelligence would have to wonder,” he went on softly, “that if my son was suffering harassment that left him vulnerable to exposure and other atrocities unknown, it is entirely possible my son’s cause of death was reported falsely?”

“I don’t know.”

“These games, this harassment. What can come of it? They would never have forced his hand, and after time I’m sure they knew this. What was left? Jail time? Perhaps,” he whispered, his voice breaking. “There was an accident.”

“Train delayed! Train delayed! Train delayed for at least four hours!” Groans and shouts followed.

The ticket man’s voice jarred her. She rose and searched the crowd for her mother and Violet and finally found them.

Talking to Billy Rankin.

Margaret’s eyebrows were knitted and her head was cocked to the side. Theda was just about to go to her when the final thought clicked in her mind.

Van Horn

Van Sickle

And the other names on those photographs. German or Dutch sounding. Mennonite.

Over the heads of the crowd, Billy Rankin spoke to her mother. Violet stood at his side, gazing, but Margaret was bothered. She kept her eyes on them and said, “Mr. Van Horn, may I presume a favor?”

“Yes, Miss?”

“I need leave here. Now. It’s very important.” She turned her head in each direction wildly. There was a back door near to them.

“Stop anyone who looks for me. My mother and sister, and especially any soldiers. Tell my mother…” What? “Tell her to be on the next train. I’ll follow them shortly. I need to speak with my father.” She laid a hand on his sleeve.

“Yes,” he said, voice not much above a whisper. “I will do this.”

“Thank you, sir.” She began to move toward the door.

“Miss Evora?”

She stopped. “Yes?”

“Was it consumption?”

She shook her head. “I don’t think so. But please leave here yourself. There’s going to be trouble, I’m afraid.” Before Van Horn could say another word, she turned the knob on the side door and pushed against the invisible hands of the wind. She wrapped her scarf over her nose and mouth and began a fast walk away from the train station. She kept her head down, desperately trying to keep the dust from her eyes. She coughed and when she raised her head to get some idea of what direction she was heading, she ran straight into the chest of a man.

“Miss Evora,” Patrick Conlin steadied her.

She pulled away and was about to run in the other direction when he grabbed her arm and said, “There’s no time for stupidity. Rankin’s in there and he’s got plans for you you’re not gonna like. Come with me now. Or stay here and find out. Which is it?”

She threw one desperate look backwards, but it was as if everything she knew had suddenly fallen from existence.

“Let’s go, Mr. Conlin.”

Read the next chapter here:

As a punster, I liked the pun with "derailed"! Great episode.

Great job Alison. Loved the action/suspense - with the dust storm going on at the same time. - Jim