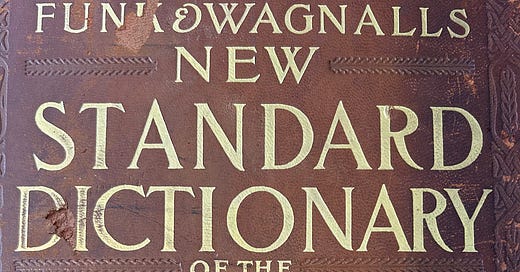

Funk and Wagnalls 1913 Dictionary

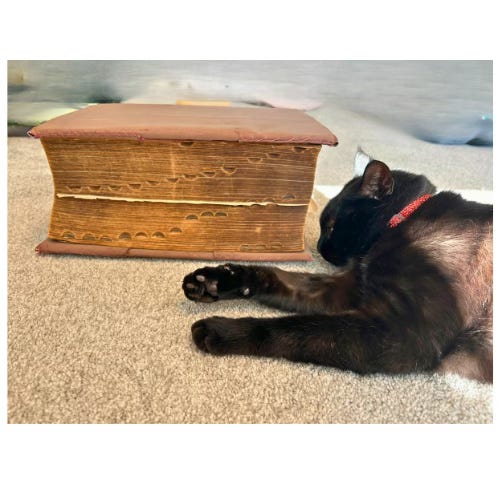

Sometimes the Writing Gods drop a historical treasure in your lap...all fifteen pounds of it!

Last year, during one of many 3a.m.-can’t-sleep Netflix scrolling sessions, I landed on The Professor and the Madman, based on the 1998 book by Simon Winchester. The story of the decades long making of the Oxford English Dictionary was surprisingly interesting, even aside from the main story featuring the outstanding performances by Sean Penn and Mel Gibson.

I raved about it to friends who either, when they found out the story was about making a dictionary, issued a polite no thanks or barked laughter. How could a dictionary, that old standby found in every house and classroom prior to 2000, be fascinating?

Rewind to a few years prior, when my neighbor, Elaine, was prepping her house for sale. She called me. “I know you’re a writer. Do you want my father’s dictionary? It’s from 1913.”

“I’ll be right over.”

An hour later, I lumbered up the street carrying a massive, fifteen-pound book that when my husband saw it, his eyes glazed over with dread. He is used to me showing up with all kinds of “antiques.” Once I came home with five bags of seventy-five-plus-year-old books from an estate sale. The next day the entire house smelled like a mildewy library basement. But this Dictionary was in great shape after having spent more than fifty-years in a place of honor on a pedestal table.

Funk and Wagnalls 1913 Dictionary has been an invaluable source for my historical fiction/fantasy novel Theda’s Time Machine which is set in 1918. Among the heavier research I conducted on Fort Riley, Kansas, and World War I American military, I wanted to be able to get the little details right, such as making sure I was accurately describing everyday things, for example, cars, in terms used in 1918. We’ve all had the experience of reading a historical fiction story and finding a term or an item that wasn’t around in that particular time period.

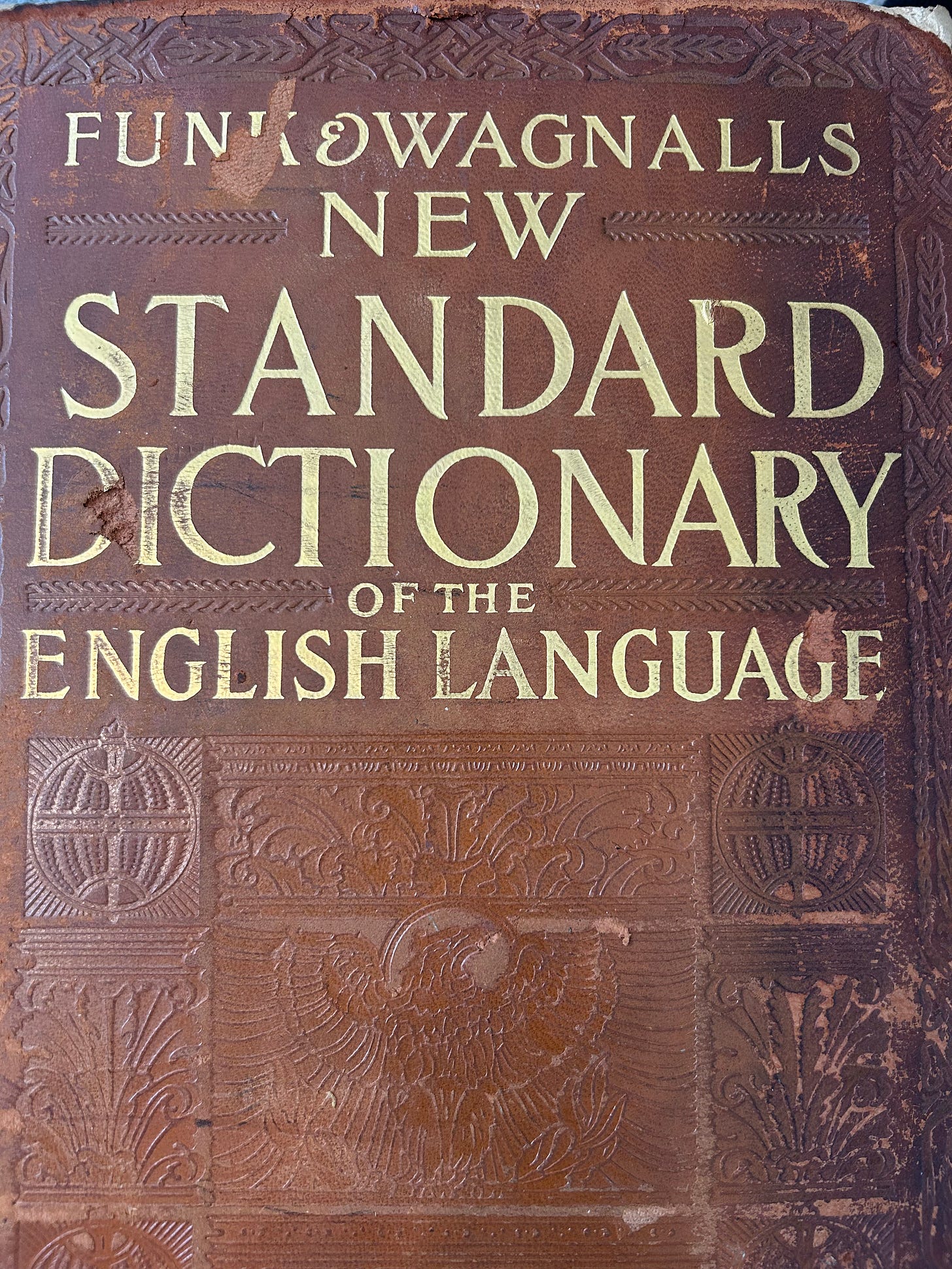

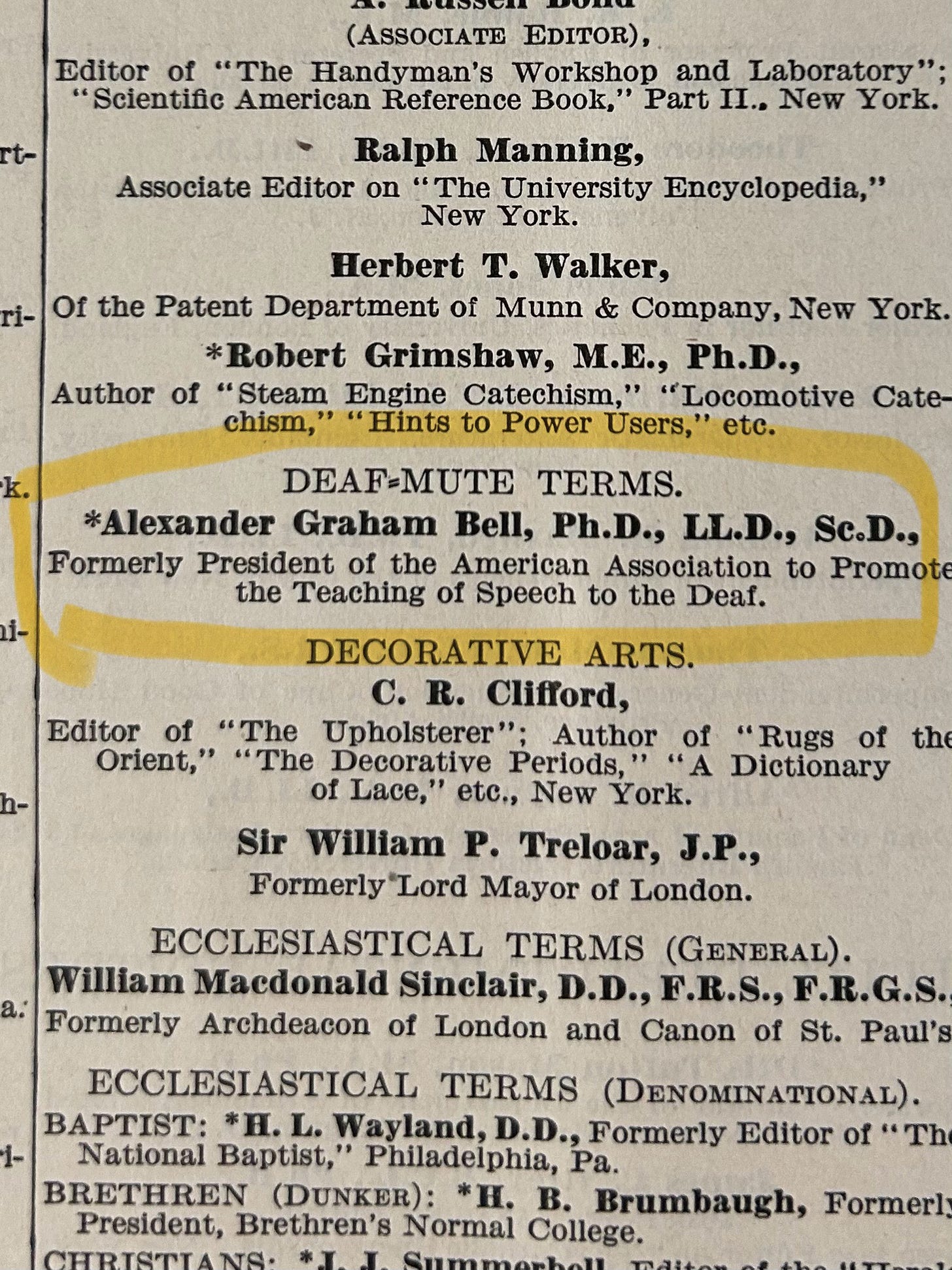

Let’s take a quick look at some interesting aspects of Funk and Wagnalls, like the Editorial Staff page, where you’ll find some famous names:

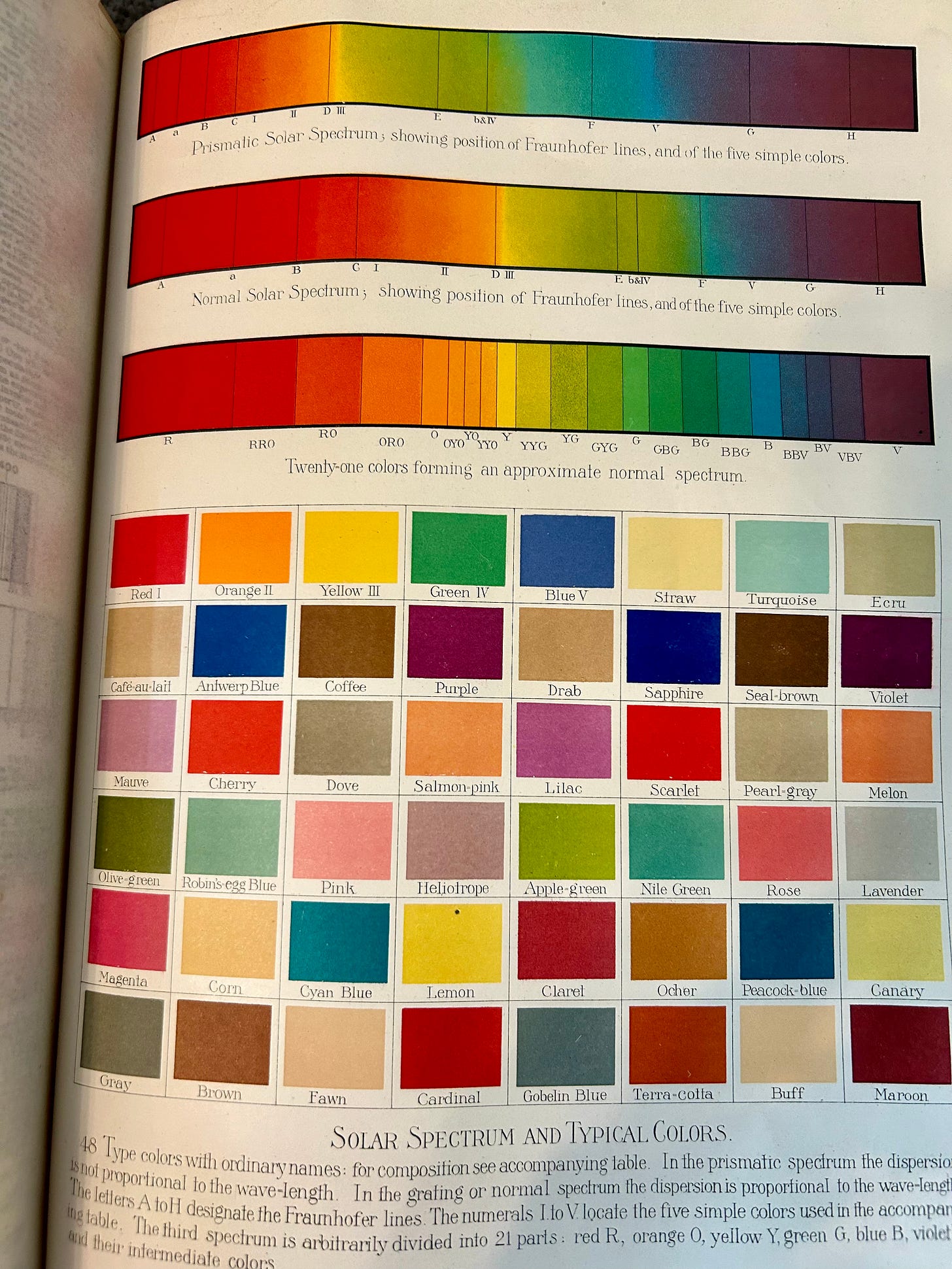

What were common names for colors? What I called lavender, my grandmother called orchid, a very 1940s term. Look at the below chart. Did any woman ever say, “I’ll take that dress in Gobelin Blue?” Maybe. Gobelin was apparently a family of dyers going back to the 15th century (Wikipedia).

An example of modern steel construction, New York’s Woolworth Building:

X-ray technology, and lungs with emphysema:

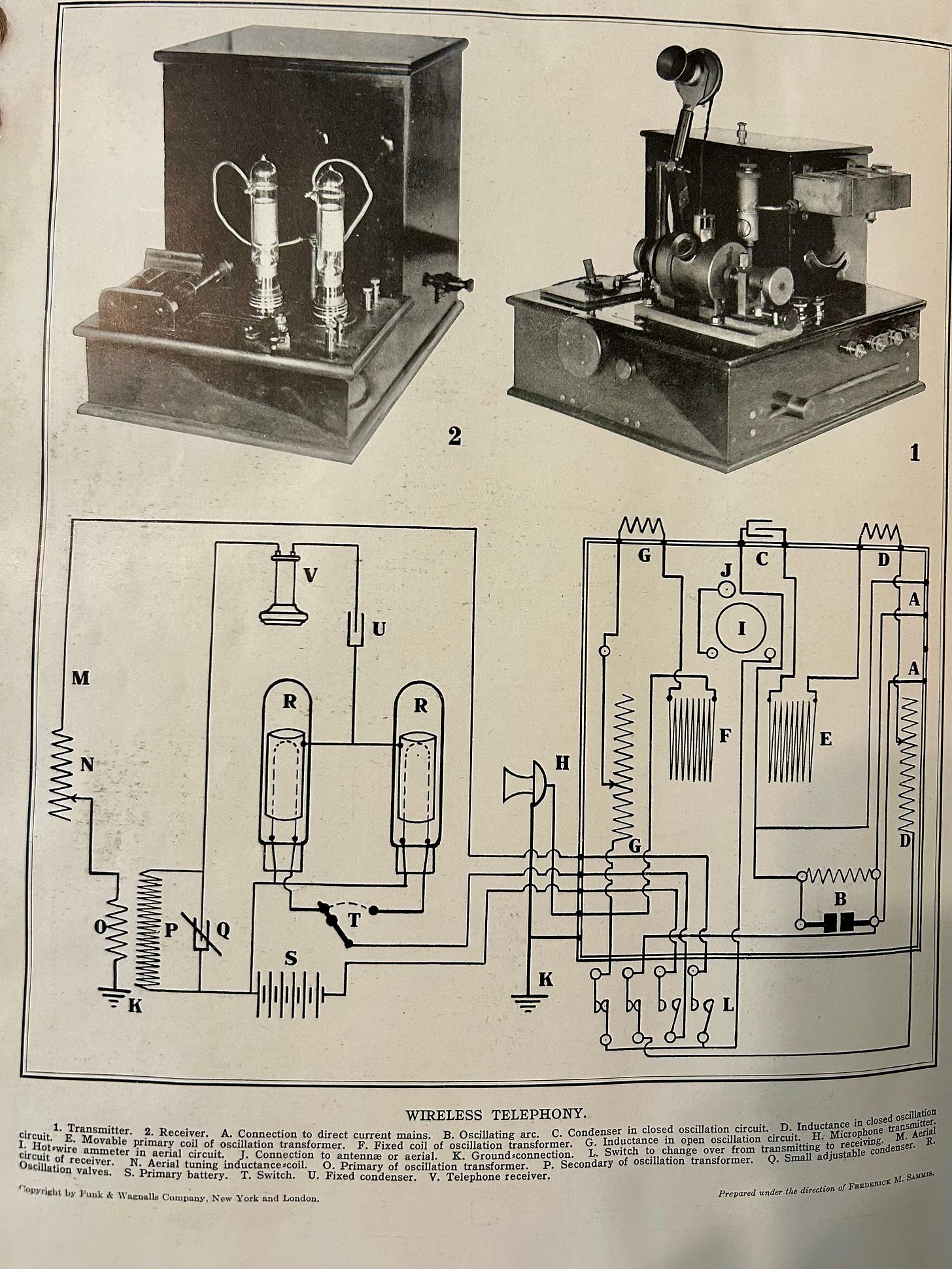

And Wireless Telephony:

Listen, bring me food and coffee and I’ll spend all day with Funk and Wagnalls!

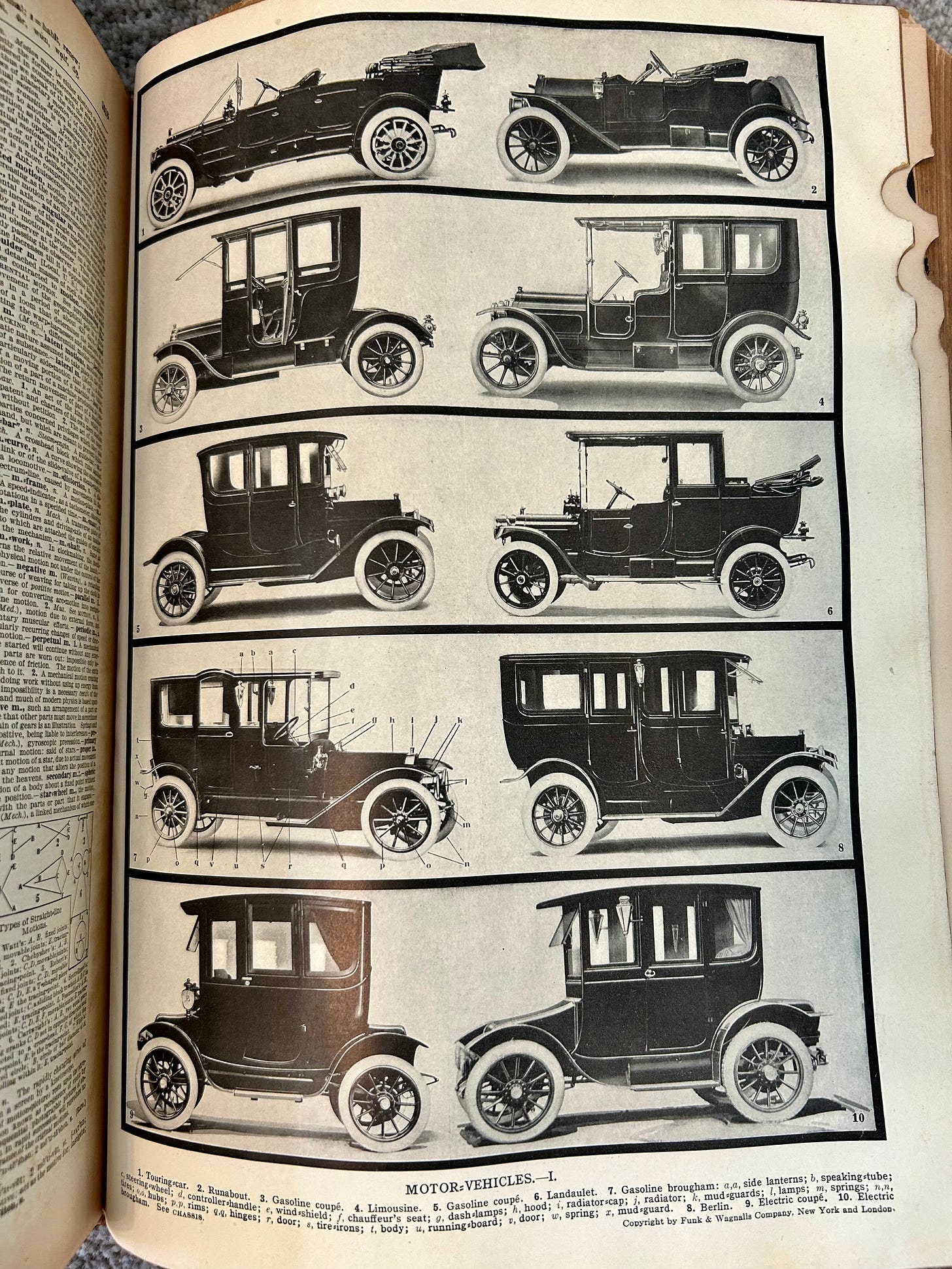

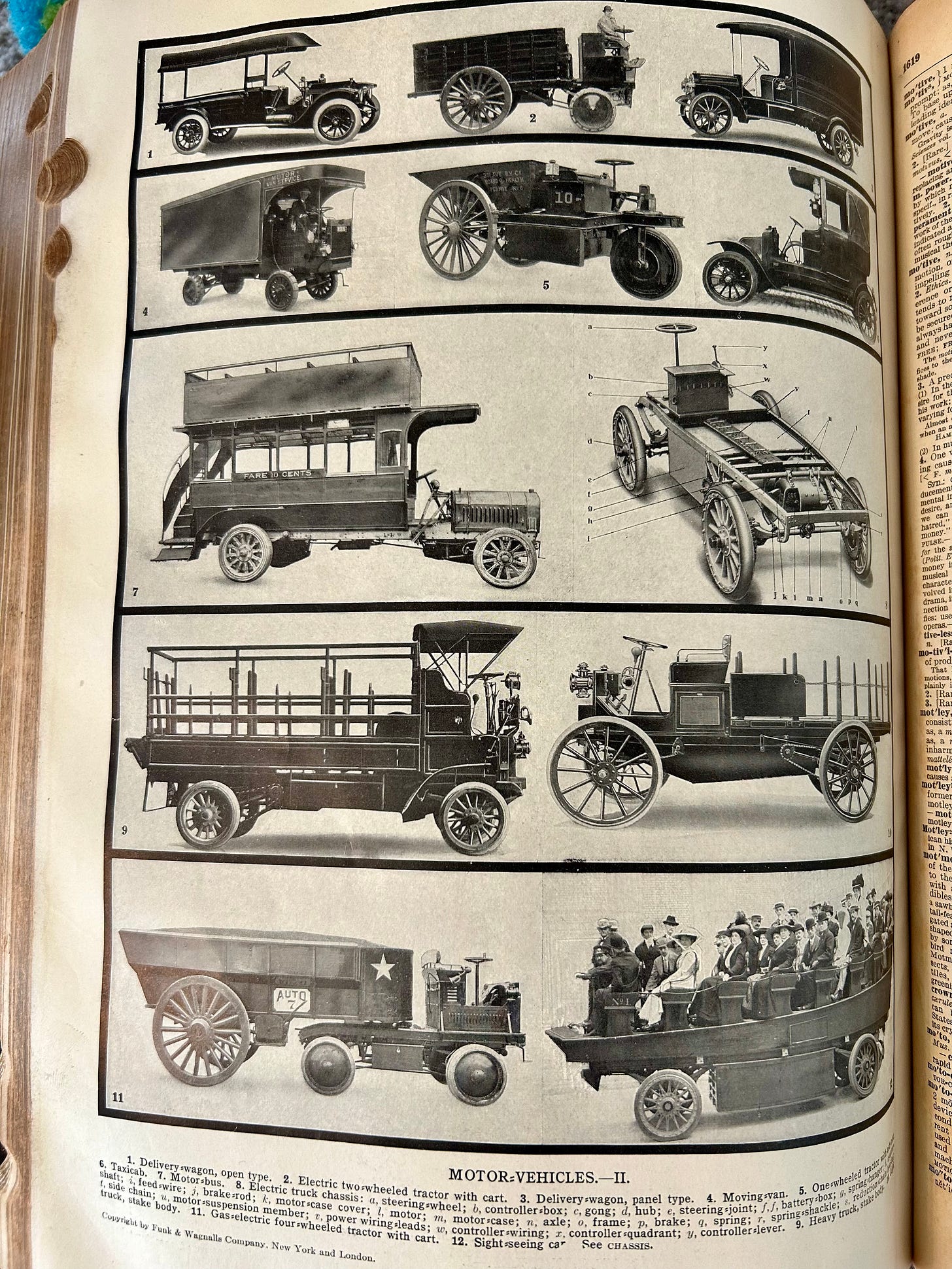

In the coming chapters, Theda’s Time Machine has a lot of action, including car and motorcycle chases. There were many details I researched. How fast was the fastest car in 1918? Common cars like the Ford Model T were able to go to 45-mph. How was a car started? If I wrote a scene where our heroine was desperately starting a car before the bad guys found her, was she turning a key or perhaps pushing a button? Cars that had to be cranked were phasing out by 1918. I wanted to make sure I had visuals in my mind and also have the language for the characters to talk about cars. In the below section from Funk and Wagnalls, the top left touring car is featured in Chapter 6, The Cherry-Red Stanley Motorcar. I used motorcar in the title because most modern readers wouldn’t recognize touring car or touring model, which is what the car technically is called. The Martin Wasp (see chapter 3, The Winter Wasp for photo), driven by Patrick Conlin, is also an example of a touring car:

But notice figure 7 (left, second from the bottom). The parts of the car are labeled, and although most of the parts are terms we still use today, there are a few different ones. Today’s driver’s seat was the chauffeur’s seat! Did that many people have chauffeurs? Main character Patrick Conlin’s father was a chauffeur for a wealthy family in the 1920s, so I’m sure he would have used the term. Headlights are called lamps. In my novel there are time traveling men from the 1940s who would use the term headlight. But if a 1918 woman like Theda talks about the car’s headlights, she’s going to call them lamps.

Another valuable page of information is in Figure 8 (middle right) in the below picture. It’s an example of the interior parts of a car and their names as of 1913.

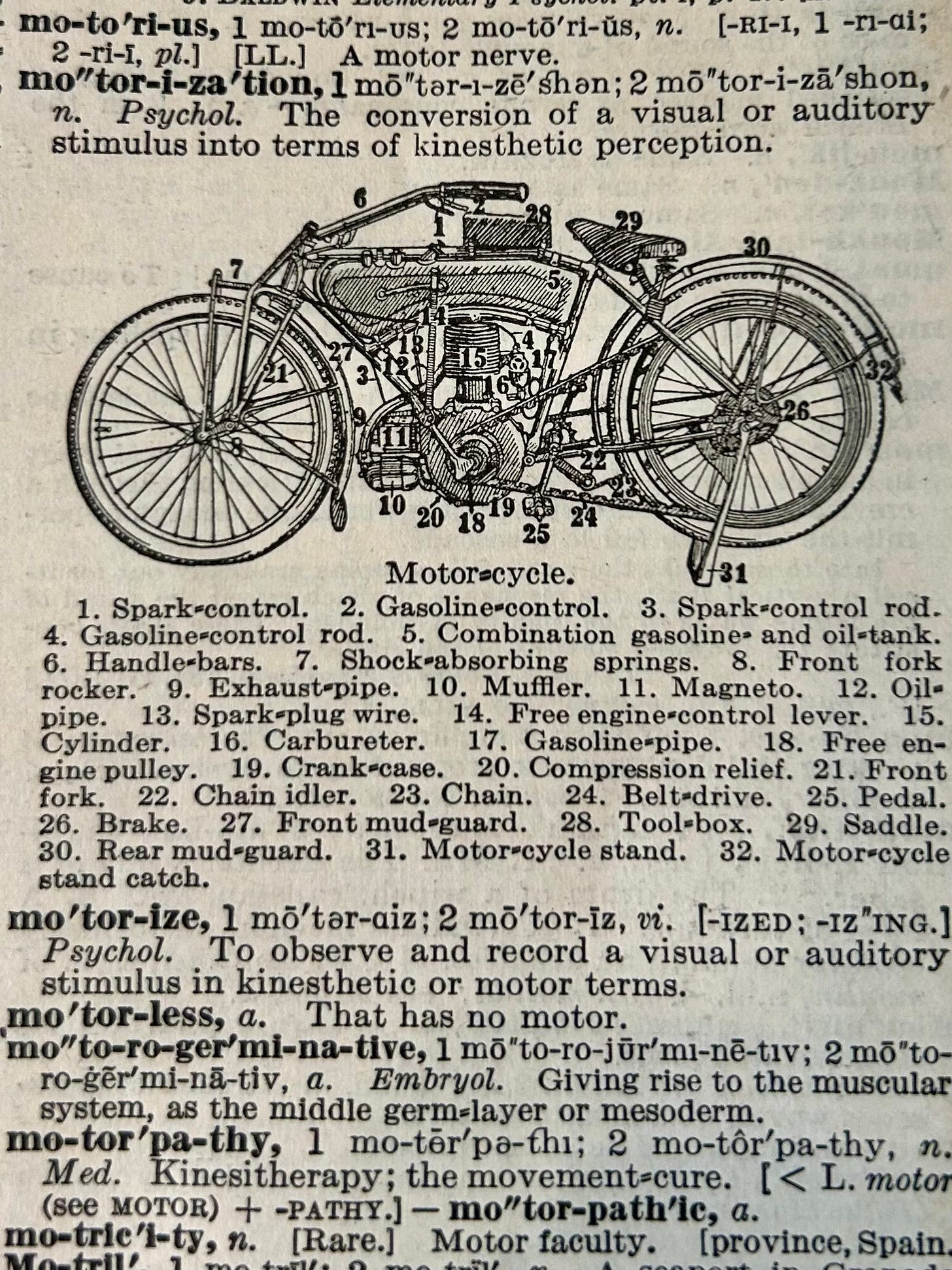

Motorcycles became widely used during the First World War. One of the main characters, Asa Jackson, rides a motorcycle. It’s a 1915 Harley-Davidson Cannonball, that looks something like this:

Where can you find Funk and Wagnalls?

I checked online and copies of this dictionary sell anywhere from $120 for ones in not-so-great condition, upwards of $500 for ones in mint condition. Spending that kind of money doesn’t make sense, and I don’t even want to think about what the shipping on this bear would be. Here at the Historical Fiction Stack, we do our research in two ways: 1. Inexpensive and 2. Focused, meaning, finding accurate information with as little time spent as possible. Yes, we all have to dive into materials and can’t take shortcuts, but most writers I know, myself included, have full time jobs and aren’t driving around in the chauffeur seat dropping money on antique dictionaries. But I did find one for $45 on Mercari.

One of the best places I find old and antique books is on those local free boards on Facebook. People get rid of books all the time, especially ones like this that take up a tremendous amount of room. I’ve even put out feelers asking if anyone is getting rid of antique books to let me know and I’ve found some great things, like a World War I book of poetry and a history by H.G. Wells that ends with the Great War. Funk and Wagnalls published dictionaries, encyclopedias and other reference books into the 1990s, so there are probably a lot out there that someone is just dying to have you take off their hands.

If any of my readers need a reference or a screen shot from this dictionary, please let me know and I’ll send you what you need.

The Great War, fast cars, time travelers and a major historical event: read Theda’s Time Machine. Start here:

I have a complete Encyclopaedia Brittanica from 1875. I HIGHLY recommend buying these old books; the knowledge is priceless, the window into a world long gone equally so. I want another encyclopaedia...anything from before 1911 (I have been told they started watering down the information in the encyclopaediae from that year onward...an example: the 1875 EB has 37 pages devoted to blackpowder...and a modern EB has a few paragraphs. Can't have folks learning how to make boomy-stuff, can we. Lawyers...friggin lawyers...)

I have Audel's Guides for plumbing and carpentry from 1926. There is so much there, so much of use, they are worth their weight in gold. I have The Golden Book of Chemistry Experiments from 1960...it teaches more and better chemistry than my college courses did. I have The Amateur Scientist from 1960; it contains real info on rocketry, building seismographs...astonishing stuff...and it was all once considered so simple as to be in the province of the amateur scientist.

Old books is da best books.

Barbed wire was invented in the late 1800s, about 40 years before WWI. So a story with a scene of a dog getting tangled in it in 1910 is quite believable.

http://npshistory.com/brochures/home/barbed-wire.pdf

https://www.invent.org/inductees/joseph-f-glidden#:~:text=Joseph%20Glidden's%20innovative%20barbed%20wire,cattle%20in%20and%20trespassers%20out.